Source: HenryGiroux

The toxic thrust of white supremacy runs

through American culture like an electric current. Jim Crow is back

without apology suffocating American society in a wave of voter

suppression laws, the elevation of racist discourse to the centers of

power, and the ongoing attempt by right-wing politicians to implement a

form of apartheid pedagogy that makes important social issues that

challenge the racial and economic status quo disappear. The cult of

manufactured ignorance now works through disimagination machines engaged

in a politics of falsehoods and erasure. Matters of justice, ethics,

equality, and historical memory now vanish from the classrooms of public

and higher education and from powerful cultural apparatuses and social

media platforms that have become the new teaching machines.

In the current era of white supremacy, the most obvious version of

apartheid pedagogy, is present in attempts by Republican Party

politicians to rewrite the narrative regarding who counts as an

American. This whitening of collective identity is largely reproduced by

right-wing attacks on diversity and race sensitivity training, critical

race programs in government, and social justice and racial issues in

the schools. These bogus assaults are all too familiar and include

widespread and coordinated ideological and pedagogical attacks against

both historical memory and critical forms of education.

The fight to censor critical, truth telling versions of American

history and the current persistence of systemic racism is part of a

larger conservative project to prevent teachers, students, journalists,

and others from speaking openly about crucial social issues that

undermine a viable democracy. Such attacks are increasingly waged by

conservative foundations, anti-public intellectuals, politicians, and

media outlets. These include right-wing think tanks such as Heritage

Foundation and Manhattan Institute, conservative scholars such as Thomas

Sowell, right-wing politicians such as Mitch McConnell, and far-right

media outlets such as City Journal, The Daily Caller, The Federalist, and Fox News. The threat of teaching children about the history and systemic nature of racism appears particularly dangerous to Fox News, which since June 5, 2020 has posited “critical race theory” as a threat in over 150 different broadcasts.[1]

What is shared by all of these individuals and cultural apparatuses is

the claim that critical race theory and other “anti-racist” programs

constitute forms of indoctrination that threatens to undermine the

alleged foundations of Western Civilization.

The nature of this moral panic is evident in the fact that 15 state

legislatures across the country have introduced bills to prevent or

limit teachers from teaching about the history of slavery and racism in

American society. In doing so, they are making a claim for what one

Texas legislator called “traditional history,” which allegedly should

focus on “ideas that make the country great.”[2] Idaho’s

lieutenant governor, Janice McGeachin, is more forthright in revealing

the underlying ideological craze behind censoring any talk by teachers

and students about race in Idaho public schools. She has introduced a

taskforce to protect young people from what she calls, with no pun

intended, “the scourge of critical race theory, socialism, communism,

and Marxism.”[3]

Such attacks are about more than

censorship and racial cleansing. They make the political more

pedagogical in that they use education and the power of persuasion as

weapons to discredit any critical approach to grappling with the history

of racism and white supremacy. In doing so, they attempt to undermine

and discredit the critical faculties necessary for students and others

to examine history as a resource in order to “investigate the core

conflict between a nation founded on radical notions of liberty,

freedom, and equality, and a nation built on slavery, exploitation, and

exclusion.”[4] The

current attacks on critical race theory, if not critical thinking

itself, are but one instance of the rise of apartheid pedagogy. This is a

pedagogy in which education is used in the service of dominant power in

order to both normalize racism, class inequities, and economic

inequality while safeguarding the interests of those who benefit from

such inequities the most. In

pursuit of such a project, they impose a pedagogy of oppression,

complacency, and mindless discipline. They ignore or downplay matters of

injustice and the common good, and rarely embrace notions of community

as part of a pedagogy that engages pressing social, economic and civic

problems. Instead of an education of civic practice that enriches the

public imagination, they endorse all the elements of indoctrination

central to formalizing and updating a mode of fascist politics.

The conservative wrath waged

against critical race theory is not only about white ignorance being a

form of bliss but is also central to a struggle over power—the power of

the moral and political imagination. White ignorance is crucial to

upholding the poison of white supremacy. Apartheid pedagogy is about

denial and disappearance–a manufactured ignorance that attempts to

whitewash history and rewrite the narrative of American exceptionalism

as it might have been framed in the 1920s and 30s when members of a

resurgent Ku Klux Klan shaped the policies of some school boards.

Apartheid pedagogy uses education as a disimagination machine to

convince students and others that racism does not exist, that teaching

about racial justice is a form of indoctrination, and that understanding

history is more an exercise in blind reverence than critical analysis.

Apartheid pedagogy aims to reproduce current systems of racism rather

than end them. Organizations such as No Left Turn in Education

not only oppose teaching about racism in schools, but also comprehensive

sex education, and teaching children about climate change, which they

view as forms of indoctrination. Without irony, they label themselves an

organization of “patriotic Americans who believe that a fair and just

society can only be achieved when malleable young minds are free from

indoctrination that suppresses their independent thought.”[5]

This is the power of ignorance in the service of civic death and a

flight from ethical and social responsibility. Kati Holloway, citing the

NYU philosopher Charles W. Mills, succinctly sums up the elements of

white ignorance. She writes:

“White ignorance,” according to NYU philosopher Charles

W. Mills, is an “inverted epistemology,” a deep dedication to and

investment in non-knowing that explains white supremacy’s highly

curatorial (and often oppositional) approach to memory, history and the

truth. While white ignorance is related to the anti-intellectualism that

defines the white Republican brand, it should be regarded as yet more

specific. According to Mills, white ignorance demands a purposeful

misunderstanding of reality—both present and historical—and then treats

that fictitious worldview as the singular, de-politicized, unbiased,

“objective” truth. “One has to learn to see the world wrongly,” under

the terms of white ignorance, Mills writes, “but with the assurance that

this set of mistaken perceptions will be validated by white epistemic

authority.”[6]

New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg reports that

right-wing legislators have taken up the cause to ban critical race

theory from not only public schools but also higher education. She

highlights the case of Boise State University, which has banned dozens

of classes dealing with diversity. She notes that soon afterwards, “the

Idaho State Senate voted to cut $409,000 from the school’s budget, an

amount meant to reflect what Boise State spends on social justice

programs.”[7] Such

attacks are happening across the United States and are not only meant

to curtail teaching about racism, sexism, and other controversial issues

in the schools, but also to impose

strict restrictions on what non-tenured assistant professors can teach

and to what degree they can be pushed to accept being both deskilled and

giving up control over the conditions of their labor.

In an egregious example of an attack on free speech and tenure itself, the

Board of Trustees at the University of North Carolina denied a tenure

position to Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, Nikole Hannah-Jones

because of her work on the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 project, “which examined the legacy of slavery in America.”[8]

The failure to provide tenure to Hannah-Jones, who is also the

recipient of a MacArthur Foundation “Genius Grant,” and an inductee into

the North Carolina Media and Journalism Hall of Fame, is a blatant act

of racism and a gross violation of academic freedom. Let’s

be clear. Hannah-Jones was denied tenure by the North Carolina Board of

Trustees because she brings to the university a critical concern with

racism that clashes with the strident political conservatism of the

board. It is also another example of a racist backlash by conservatives

who wish to deny that racism even exists in the United States, never

mind that it should even by acknowledged in the classrooms of public and

higher education.

This is a form of “patriotic education” being put in place by a

resurgence of those who support Jim Crow power relations and want to

impose pedagogies of repression on students in the classroom. This type

of retribution is part of a longstanding politics of fear, censorship

and academic repression that has been waged by conservatives since the

student revolts of the 1960s.[9]

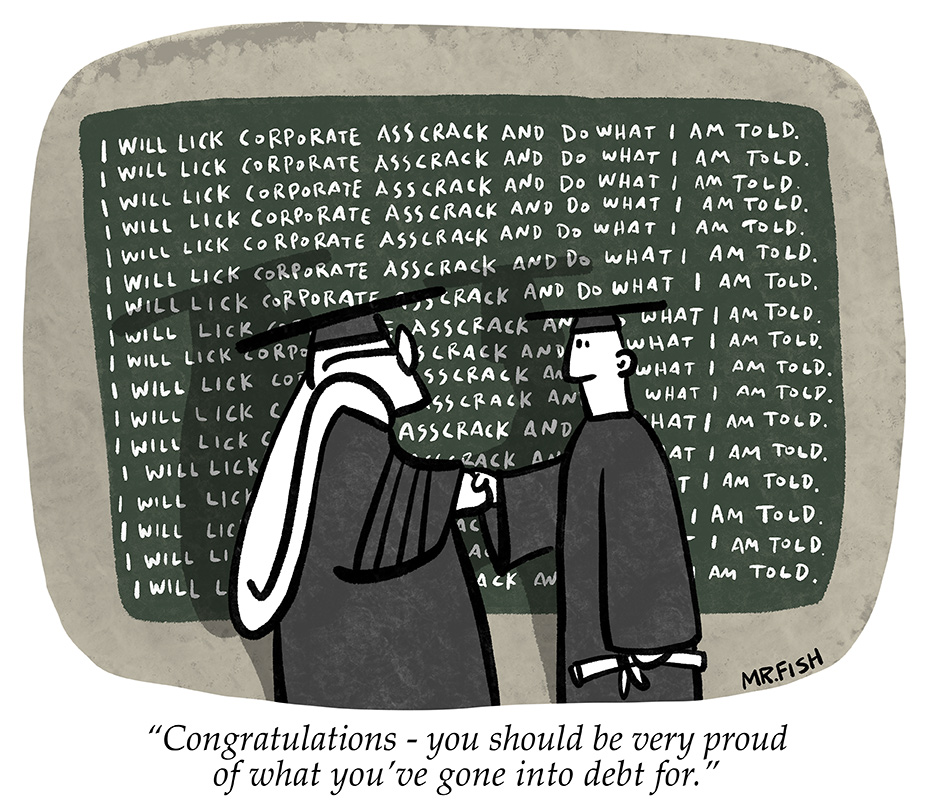

It is also part of the ongoing corporatization of the university in

which business models now define how the university is governed, faculty

are reduced to part-time workers, and students are viewed as customers

and consumers.[10]

Equally important, Hannah-Jones’ case is an updated and blatant

attack on the ability and power of faculty rather than Boards of

Trustees to make decisions regarding both faculty hiring and the crucial

question who decides how tenure is handled in a university.[11]

Keith E. Whittington and Sean Wilentz are right in stating that the

Board’s actions to deny Hannah-Jones a tenured professorship are about

more than a singular violation of faculty rights, academic freedom, and

an attack on associated discourses relating to critical race theory.

They write:

For the Board of Trustees to interfere unilaterally on

blatantly political grounds is an attack on the integrity of the very

institution it oversees. The perception and reality of political

intervention in matters of faculty hiring will do lasting damage to the

reputation of higher education in North Carolina — and will embolden

boards across the country similarly to interfere with academic

operations of the universities that they oversee.[12]

Holding critical ideas has

become a liability in the contemporary neoliberal university. Also at

risk here is the relationship between critical thinking, civic values,

and historical remembrance in the current attempts to suppress not just

voting rights but also dangerous memories, especially regarding the

attack on Critical Race Theory. David Theo Goldberg has brilliantly

outlined how the war on Critical Race Theory and other anti-racist

programs is designed largely to eliminate the legacy and persistent

effects of systemic racial injustice and its underlying structural,

ideological, and pedagogical fundamentals and components. This is

apartheid pedagogy with a vengeance. As Goldberg writes:

First, the coordinated conservative attack on CRT is

largely meant to distract from the right’s own paucity of ideas. The

strategy is to create a straw house to set aflame in order to draw

attention away from not just its incapacity but its outright refusal to

address issues of cumulative, especially racial, injustice…. Second, the

conservative attack on CRT tries to rewrite history in its effort to

neoliberalize racism: to reduce it to a matter of personal beliefs and

interpersonal prejudice. … On this view, the structures of society bear

no responsibility, only individuals. Racial inequities today are …not

the living legacy of centuries of racialized systems…. Third, race has

always been an attractive issue for conservatives to mobilize around.

They know all too well how to use it to stoke white resentment while

distracting from the depredations of conservative policies for all but

the wealthy.[13]

The public imagination is now in crisis. Radical uncertainty has

turned lethal. In the current historical moment, tyranny, fear, and

hatred have become defining modes of governance and education.

Right-wing politicians bolstered by the power of corporate controlled

media now construct ways of thinking and feeling that prey on the

anxieties of the isolated, disenfranchised, and powerless. This

is a form of apartheid pedagogy engineered to substitute

disillusionment and incoherence for a sense of comforting ignorance, the

thrill of hyper-masculinity, and the security that comes with the

militarized unity of the accommodating masses waging a war on democracy.

The public imagination is formed through habits of daily life, but only

for the better when such experiences are filtered through the ideals

and promises of a democracy. This is no longer true. Under neoliberal

fascism, the concentration of power in the hands of a ruling elite has

ensured that any notion of change regarding equality and justice is now

tainted, if not destroyed, as a result of what Theodor Adorno called a

retreat into apocalyptic bombast marked by “an organized flight of

ideas.”[14]

Violence in the United States has become a form of domestic

terrorism; it is omnipresent and works through complex systems of

symbolic and institutional control. It extends from the prison and

school to the normalizing efforts of cultural apparatus that saturate an

image-based culture. Violence registers itself in repressive policies,

police brutality, and in an ongoing process of exclusion and

disposability. It is also present in the weaponization of ideas and the

institutions that produce them through forms of apartheid pedagogy. Fear

now comes in the form of both armed police and repressive modes of

education. As the famed artist Isaac Cordal observes, “We live in

societies….that use fear in order to make people submissive….Fear bends

us [and makes us]vulnerable to its desires….Our societies have been

built on violence, and that heritage, that colonial hangover which is

capitalism today still remains.”[15] Under gangster capitalism’s system of power, the poverty of the civic and political imagination is taking its last breath.

Authoritarian societies do more than censor and subvert the truth, they also shape collective consciousness and punish those who engage in dangerous thinking.[16]

For instance, the current plague of white supremacy fueling neoliberal

fascism is rooted not only in structural and economic forms of

domination, but also intellectual and pedagogical forces, making clear

that education is central to politics. It also points to the urgency of

understanding that white supremacy is first and foremost a struggle over

agency, assigned meanings, and identity—over what lives count and whose

don’t. This is a politics and pedagogy that often leaves few historical

traces in a culture of immediacy and manufactured ignorance.

The emergent and expanding presence of white supremacy and fascist

politics disappear easily in a culture dominated by the endless images

of spectacularized violence that fill screen culture with mass

shootings, police violence, and racist attacks on Blacks and Asian

Americans in the post-Trump era. Disconnected and decontextualized such

images vanish in an image-based culture of shock, entertainment, and

organized forgetting. When critical ideas come to the surface,

right-wing politicians and pundits attack dissidents as un-American and

the oppositional press as “an enemy of the American people.” They also

attempt to impose a totalitarian notion of “patriotic education” on

public schools and higher education and censor academics who criticize

systemic abuses.[17]

As is well known, former President Trump, waged a relentless attack

on the media and in ways too similar to ignore echoed written and spoken

sentiments that Hitler used in his rise to power.[18]

In this instance, culture, increasingly shaped by an apartheid

pedagogy, has turned oppressive and must be addressed as a site of

struggle while working in tandem with the development of an ongoing

massive resistance movement. This

suggests the need for a more comprehensive understanding of politics and

the power of the educational force of the culture. Such connections

necessitate closer attention be given to the educational and cultural

power of a neoliberal corporate elite who use their mainstream and

social media platforms to shape pedagogically the collective

consciousness of a nation in the discourse and relations of hate,

bigotry, ignorance, and conformity.

America’s slide into a fascist politics demands a revitalized

understanding of the historical moment in which we find ourselves, along

with a systemic critical analysis of the new political formations that

mark this period. Part of this challenge is to create a new language and

mass social movement to address and construct empowering terrains of

education, politics, justice, culture, and power that challenge existing

systems of racist violence and economic oppression. The beginning of

such a political and pedagogical strategy can be found in the Black

Lives Matter movement and its alignment with other movements fighting

against authoritarianism. The Black Lives Matter movement teaches us

“that eradicating racial oppression ultimately requires struggle against

oppression in all of its forms…[especially] restructuring America’s

economic system.”[19]

This is especially important as those groups marginalized by class,

race, ethnicity, and religion have become aware of how much in this new

era of fascist politics they have lost control over the economic,

political, pedagogical, and social conditions that bear down on their

lives. Visions have become dystopian, devolving into a sense of being

left out, abandoned, and subject to increasing systems of terror and

violence. These issues can no longer be viewed as individual problems

but as manifestations of a broader failure of politics. Moreover, what

is needed is not a series of stopgap reforms limited to particular

institutions or groups, but a radical restructuring of the entirety of

U.S. society.

The call for a socialist democracy demands the creation of visions,

ideals, institutions, social relations, and pedagogies of resistance

that enable the public to imagine a life beyond a social order in which

racial, class, gender, and other forms of violence produce endless

assaults on the environment, systemic police violence, a culture of

ignorance and cruelty. Such

challenges must also address the assault on the public and civic

imagination, mediated through the elevation of war, militarization,

violent masculinity, and the politics of disposability to the highest

levels of power. Capitalism is a death driven machine that that

infantilizes, exploits, and devalues human life and the planet itself.

As market mentalities and moralities tighten their grip on all aspects

of society, democratic institutions and public spheres are being

downsized, if not altogether disappearing, along with the informed

citizens without which there is no democracy.

Any viable pedagogy of resistance needs to create the educational and

pedagogical tools to produce a radical shift in consciousness, capable

of both recognizing the scorched earth policies of neoliberal

capitalism, and the twisted ideologies that support it. This shift in

consciousness cannot take place without pedagogical interventions that

speak to people in ways in which they can recognize themselves, identify

with the issues being addressed, and place the privatization of their

troubles in a broader systemic context.[20]

Niko Block gets it right in arguing for a “radical recasting of the

leftist imagination,” in which the concrete needs of people are

addressed and elevated to the forefront of public discussion in order to

confront and get ahead of the crises of our times. He writes:

the crises of the twenty-first century call for a radical

recasting of the leftist imagination. This process involves building

bridges between the real and the imaginary, so that the path to

achieving political goals is plain to see. Accordingly, the articulation

of leftist goals must resonate with people in concrete ways, so that it

becomes obvious how the achievement of those goals would improve their

day-to-day lives. The left, in this sense, must appeal to people’s

existing identities and not condescend the general public as victims of

“false consciousness.” All this means building movements of continual

improvement and refusing to ask already-vulnerable people for short-term

losses on the abstract promise of long-term gains. This project also

demands that we understand precisely why right-wing ideology retains a

popular appeal in so many spaces.[21]

A pedagogy of resistance must be on the side of hope and civic

courage in order to fight against a paralyzing indifference, grave

social injustices, and mind deadening attacks on the public imagination.

At stake here is the struggle for a new world based on the notion that

capitalism and democracy are not the same, and that we need to

understand the world, how we think about it and how it functions, in

order to change it. In the spirt of Martin Luther King, Jr’s call for a

more comprehensive view of oppression and political struggle, it is

crucial to address his call to radically interrelate and restructure

consciousness, values, and society itself. In this instance, King and

other theorists, such as Saskia Sassen, call for a language that

ideological ruptures and changes the nature of the debate. This suggests

more than simply a rhetorical challenge to the economic conditions that

fuel neoliberal capitalism. There is also the need to move beyond

abstract notions of structural violence and identify and connect the

visceral elements of violence that bear down on and “constrain agency

through the hard surfaces of [everyday] life.”[22]

We live in an era in which the distinction between the truth and

misinformation is under attack. Ignorance has become a virtue, and

education has become a tool of repression that elevates self-interest

and privatization to central organizing principles of both economics and

politics. The socio-historical conditions that enable racism, systemic

inequality, anti-intellectualism, mass incarceration, the war on youth,

poverty, state violence, and domestic terrorism must be remembered in

the fight against that which now parades as ideologically normal.

Historical memory and the demands of moral witnessing must become part

of a deep grammar of political and pedagogical resistance in the fight

against neoliberal capitalism and other forms of authoritarianism.

A pedagogy of resistance necessitates a language that connects the

problems of systemic racism, poverty, militarism, mass incarceration,

and other injustices as part of a totalizing structural, pedagogical,

and ideological set of condition endemic to capitalism in its updated

merging of neoliberalism and fascist politics. Audre

Lorde was right in her insistence that “There is no such thing as a

single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

We don’t need master narratives, but we do need a recognition that

politics can only be grasped as part of a social totality, a struggle

rooted in overlapping differences that bleed into each other. We need

relational narratives that bring together different struggles for

emancipation and social equality.

Central to any viable notion of pedagogical resistance is the courage

to think about what kind of world we want—what kind of future we want

to build for our children. These are questions that can only be

addressed when we address politics and capitalism as part of a general

crisis of democracy. This challenge demands the willingness to develop

an anti-capitalist consciousness as the basis for a call to action, one

willing to dismantle the present structure of neoliberal capitalism.

Chantal Mouffe is correct in arguing that “before being able to

radicalize democracy, it is first necessary to recover it,” which means

first rejecting the commonsense assumptions that capitalism and

democracy are synonymous.[23]

Clearly, such a project cannot

combat poverty, militarism, the threat of nuclear war, ecological

devastation, economic inequality, and racism by leaving capitalism’s

system of power in place. Nor can resistance be successful if it limits

itself to the terrain of critique, criticism, and the undoing of

specific oppressive systems of representation. Pedagogies of resistance

can teach people to say no, become civically literate, and create the

conditions for individuals to develop a critical political

consciousness. The challenge here is to make the political more

pedagogical. This suggests analyzing how the forces of gangster

capitalism impact consciousness, shape agency, and normalize the

internalization of oppression. Such a project suggest a politics willing

to transcend the fragmentation and politicized sectarianism all too

characteristic of left politics in order to embrace a Gramscian notion

of “solidarity in a wider sense.”[24]

There is ample evidence of such solidarity in the policies advocated by

the progressive Black Lives Matter protest, the call for green

socialism, movements for health as a global right, growing resistance

against police violence, emerging ecological movements such as the

youth-based Sunrise movement, the Poor People’s Campaign, the massive

ongoing strikes waged by students and teachers against the defunding and

corporatizing of public education, and the call for resistance from

women across the globe fighting for reproductive rights.

What must be resisted at all costs, is an “apartheid pedagogy,”

rooted in the notion that a particular mode of oppression, and those who

bear its weight, offers political guarantees.[25]

Identifying different modes of oppression is important, but it is only

the first step in moving from addressing the history and existing

mechanisms that produce such trauma to developing and embracing a

politics that unites different identities, individuals, and social

movements under the larger banner of democratic socialism. This is a

politics that refuses the easy appeals of ideological silos which

“limits access to the world of ideas and contracts the range of tools

available to would-be activists.”[26]

The only language provided by neoliberalism is the all-encompassing

discourse of the market and the false rhetoric of unencumbered

individualism, making it difficult for individuals to translate private

issues into broader systemic considerations. Mark Fisher was right in

claiming that capitalist realism not only attempts to normalize the

notion that there is not only no alternative to capitalism, but also

makes it “impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.” [27]

This is a formula for losing hope because it insists that that the

world cannot change. It also has the hollow ring of slow death.

The urgency of the historical moment demands new visions of social

change, an inspired and energized sense of social hope, and the

necessity for diverse social movements to unite under the collective

struggle for democratic socialism. The debilitating political pessimism

of neoliberal gangster capitalism must be challenged as a starting point

for believing that rather than being exhausted, the future along with

history is open and now is the time to act. It is time to make possible

what has for too long been declared as impossible.

Notes.

1) Adam Harris, “The GOP’s ‘Critical Race Theory’ Obsession,” The Atlantic (May 7, 2021). Online: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2021/05/gops-critical-race-theory-fixation-explained/618828/ ↑

2) Kate McGee, “Texas’ Divisive Bill Limiting How Students Learn

About Current Events And Historic Racism Passed By Senate,” Texas Public

Radio (May 23, 2021). Online:

https://www.tpr.org/education/2021-05-23/texas-divisive-bill-limiting-how-students-learn-about-current-events-and-historic-racism-passed-by-senate

↑

3) Julie Carrie Wong, “The fight to whitewash US history: ‘A drop of poison is all you need’,” The Guardian (May 25, 2021). Online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/may/25/critical-race-theory-us-history-1619-project ↑

4) George Sanchez and Beth English, “OAH Statement on White House Conference on American History,” Organization of American History (September 2020). Online: https://www.oah.org/insights/posts/2020/september/oah-statement-on-white-house-conference-on-american-history/#:~:text=History%20is%20not%20and%20cannot%20be%20simply%20celebratory.&text=The%20history%20we%20teach%20must,slavery%2C%20exploitation%2C%20and%20exclusion. ↑

5) Editorial, “Mission goals and objectives,” No Left Turn in Education, (2021). Online: https://noleftturn.us/ ↑

6) Kali Holloway, “White Ignorance Is Bliss—and Power,” Yahoo! News (May 24, 2021). Online: https://news.yahoo.com/white-ignorance-bliss-power-080232025.html ↑

7) Michelle Goldberg, “The Social Justice Purge at Idaho College,” New York Times. (March 26, 2021). Online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/26/opinion/free-speech-idaho.html ↑

8) Katie Robertson, “Nikole Hannah-Jones Denied Tenure at University of North Carolina,” New York Times (May 19, 2021). Online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/19/business/media/nikole-hannah-jones-unc.html ↑

9) Michelle Goldberg, “The Campaign to Cancel Wokeness,” New York Times. (February 26, 2021). Online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/26/opinion/speech-racism-academia.html ↑

10) Henry A. Giroux, Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education (Chicago: Haymarket Press, 2020). ↑

11) Silke-Marie Weineck, “The Tenure Denial of Nikole Hannah-Jones Is Craven and Dangerous,” The Chronicle of Higher Education (May 20, 2021). Online: https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-tenure-denial-of-nikole-hannah-jones-is-craven-and-dangerous ↑

12) Keith E. Whittington and Sean Wilentz, “We Have Criticized Nikole

Hannah-Jones. Her Tenure Denial Is a Travesty,” The Chronicle of Higher

Education (May 24, 2021). Online:

https://www.chronicle.com/article/we-have-criticized-nikole-hannah-jones-her-tenure-denial-is-a-travesty?utm_source=Iterable&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=campaign_2377858_nl_Afternoon-Update_date_20210524&cid=pm&source=ams&sourceId=11167

↑

13) David Theo Goldberg, “The War on Critical Race Theory,” Boston Review (May 7, 2021). Online: http://bostonreview.net/race-politics/david-theo-goldberg-war-critical-race-theory ↑

14) Volker Weiss, “afterword,” in Theodor W. Adorno, Aspects of the New Right-Wing Extremism (London: Polity, 2020), p. 61. ↑

15) Brad Evans and Isaac Cordal, “Histories of Violence: Look Closer

at the World, There You Will See,” Los Angeles Review of Books,”

December 28, 2020). Online: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/histories-of-violence-look-closer-at-the-world-there-you-will-see/ ↑

16) Henry A. Giroux, Dangerous Thinking in the Age of the New Authoritarianism (New York: Routledge, 2015). ↑

17) Charlotte Klein, “Mitch McConnell: Don’t Teach Our Kids That America Is Racist,” Vanity Fair (May 4, 2021). Online: https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2021/05/mitch-mcconnell-dont-teach-our-kids-that-america-is-racist; Michael Crowley, “Trump Calls for ‘Patriotic Education’ to Defend American History From the Left,” New York Times (September 17, 2020). Online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/17/us/politics/trump-patriotic-education.html ↑

18) Editorial, “Trump’s crusade against the media is a chilling echo of Hitler’s rise,” Las Vegas Sun (August 14, 2017). Online: https://lasvegassun.com/news/2017/aug/14/trumps-crusade-against-the-media-is-a-chilling-ech/; for a larger examination of this issue, see Federico Finchelstein, A Brief History of Fascist Lies (Oakland: University of California Press, 2020). ↑

19) Lacino Hamilton, “This is going to Hurt,” The New Inquiry (April 11, 2017). Online: https://thenewinquiry.com/this-is-going-to-hurt/ ↑

20) See Robert Latham, A. T. Kingsmith, Julian von Bargen and Niko Block, eds Challenging the Right, Augmenting the Left–Recasting Leftist Imagination (Winnipeg, Canada: Fernwood Publishing, 2020). ↑

21) Nico Block, “Augmenting the Left: Challenging the Right, Reimagining Transformation,” Socialist Project: the Bullet

(August 31, 2020). Online:

https://socialistproject.ca/2020/08/augmenting-the-left-challenging-the-right-reimagining-transformation/

↑

22) David Graeber, “Dead Zones of the Imagination,” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2 (2012), p. 105 ↑

23) Chantal Mouffe, For a Left Populism, [London: Verso, 2018], p. 37. ↑

24) Institute for Critical Social Analysis, “A Window of Opportunity for Leftist Politics?” Socialist Project: the Bullet (August 3, 2020). Online: https://socialistproject.ca/2020/08/window-of-opportunity-for-leftist-politics/ ↑

25) I have taken the notion of “apartheid pedagogy” from Adam Shatz, “Palestinianism” London Review of Books (43:9 (May 6, 2021), p. 28. Online: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v43/n09/adam-shatz/palestinianism ↑

26) Robin D.G. Kelley, “Black Study, Black Struggle – final response,” Boston Review, (March 7, 2016). Online: http://bostonreview.net/forum/black-study-black-struggle/robin-d-g-kelley-robin-d-g-kelleys-final-response ↑

27) Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2009), p. 2. I would be useful on this issue to read the brilliant Stanley Aronowitz, especially The Death and rebirth of American Radicalism (New York: Routledge, 1996), ↑

Henry A. Giroux currently holds the

McMaster University Chair for Scholarship in the Public Interest in the

English and Cultural Studies Department and is the Paulo Freire

Distinguished Scholar in Critical Pedagogy. His most recent books are America’s Education Deficit and the War on Youth (Monthly Review Press, 2013), Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education (Haymarket Press, 2014), The Public in Peril: Trump and the Menace of American Authoritarianism (Routledge, 2018), and the American Nightmare: Facing the Challenge of Fascism

(City Lights, 2018), On Critical Pedagogy, 2nd edition (Bloomsbury),

and Race, Politics, and Pandemic Pedagogy: Education in a Time of Crisis

(Bloomsbury 2021):His website is www. henryagiroux.com.