Source: The Baffler

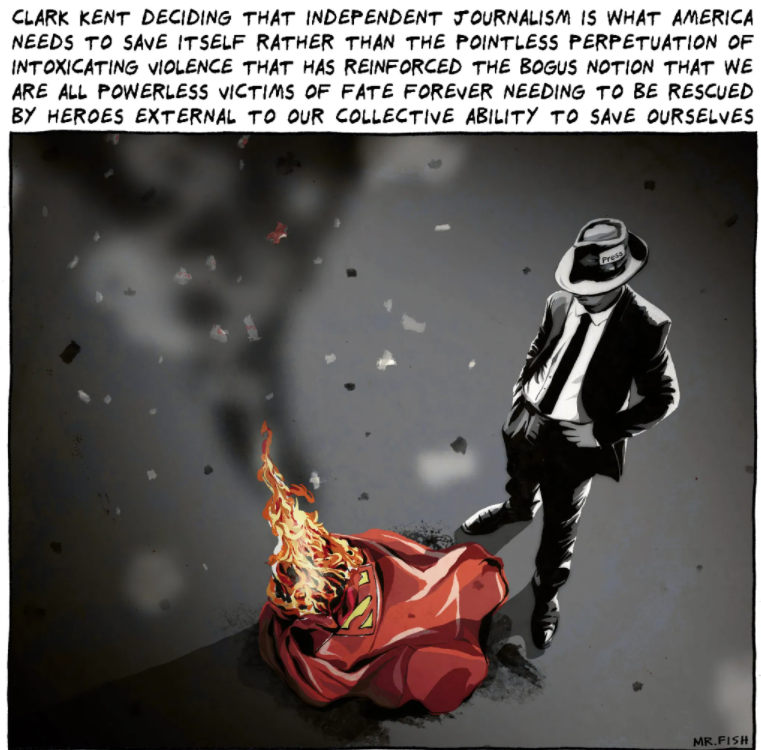

One of the immediate casualties of Trump’s rise to power, or so we were constantly told, was the truth. Scores of pundits appeared on television and discussed Trump’s habit of obscuring or ignoring the truth altogether. Journalists here and abroad catalogued and constantly updated Trump’s register of lies; we were informed in tones both solemn and (let’s be honest) ecstatic that no inhabitant of the White House had ever lied so fluently. A rabble of Democratic candidates for the presidency made the restoration of truth a centerpiece of their campaigns. Indeed, candidate Joe Biden often ended his stump speeches with a version of the same refrain: “We choose hope over fear,” he’d declaim. “Unity over division. Science over fiction. And truth over lies.”

At the beginning of Trump’s first campaign for the presidency I found myself among those who were shocked by his cavalier relationship with the truth. I agreed in a distracted almost thoughtless way that Trump was a liar, that he was shameless and detached from reality, that he frequently went too far. But as the clamor heightened, and then as national figures such as Biden argued that what our society required more than anything else was a return to the status quo, a recommitment to a supposedly common conception of the truth, I began to wonder if that was really such a good idea.

The Emperor of Ice Cream

I must have been eleven years old. Maybe twelve. I was out with my father selling ice cream. My father had recently started his own business, something he had dreamed about his whole life. He had purchased a mail truck and converted it into an ice cream truck, and he spent his summer days driving up and down the streets of Ogden, Utah, where we lived. My siblings and I accompanied him on his trips through the city, but for some reason it was only him and me this time. I could not remember a time when I’d been happier.

Someone flagged us down and my father pulled over to the curb. An older white man approached our truck. We’d never met him before, but he smiled, and my father, ever the salesman, smiled back and told him our specials of the day. The man stroked his chin and selected an ice cream. He handed my father a twenty-dollar bill. I found the ice cream and passed it to the man while my father collected the change. He handed it over and thanked the man for his purchase, and as he was putting the truck into gear the man held up his hand and shook his head. “This isn’t enough,” he said. I quickly glanced at my dad, and his contented expression had not changed, save for a slight wrinkle in his brow. “Excuse me?” my father said. “This isn’t enough,” the man said again. “The change. I gave you a hundred and this ice cream was only seventy-five cents. You owe me a lot more.”

I was completely confused. I reached for the twenty-dollar bill where it lay in the cash box at the front of the truck and passed it to my father but he ignored me. His face had shifted by now. I knew what his face was saying though I didn’t have a word for it then. I do now. Resignation. “Please,” my father said, as calm as I’d ever heard him. “Maybe some other day I could do this, but not today.” The man smiled again, and I could tell that this was actually his true smile, that what he had offered us before was, well, a lie. “I don’t care about your sad story,” the man said, or something like this. I’m not sure about any of this dialogue because to this day my memory of this incident is clouded with anger. I remember my father quietly insisting that he had given the man the proper change, and the man growing angrier, an unstated threat murmuring just beneath the surface of his words. Finally my father grabbed the cashbox and I grabbed his arm at the same moment and pleaded with my eyes. My father shook my hand off and counted out all the money we had made, starting with the twenty dollars the man had given us, a few tens, a few singles. Not enough. My father gave the man all our money. “That’s all I have,” he said. The man counted it slowly, then looked up at us. I wanted to choke him. The man’s anger was gone, his smile was back, but dimmer. He had no need to gloat. He was white and we were Black. He had power and we had none. “This’ll do for now,” he said, folding up the bills and tucking them into his breast pocket. “I’ll get the rest when I see you next.” My father ignored him and screeched away.

Dad drove us to a parking lot. He switched off the ignition and placed his head on the steering wheel. He did not move for many minutes. I didn’t know what to do, so I rubbed his back. His shirt was sticky with sweat and heat. He eventually sat up and gave me a stern look. I knew what he was saying—this was between him and me. Then he drove back out and we began selling ice cream once more. He was just as jovial as he had been before, but we remained outside longer than normal, well after dark, and when we arrived home, he proudly showed Mom our haul. “A little less than yesterday,” he said. “I’ll do better tomorrow.”

For years I was deeply ashamed of the way my father had handled the situation, and I imagined how I would have responded if I were in his shoes. In my fantasies I was a tiny Nigerian-American Bruce Lee, nunchucking the man into brutal submission. Now, of course, I get it. What my father instantly understood was that our rogue customer held our lives in his hand. More than that, he was the master of our reality. All he had to do was place a call to the city and complain that we had somehow mistreated him and my father would lose everything—his business, his ability to pay the mortgage and feed his family, all of it. This man had power and we did not, so he had the privilege of deciding what was true.

The Other Side of Power

America has always been a country of alternative facts. Perhaps Trump’s most important and lasting contribution to the American political dialogue was to expand the number of people who now realize what many of us—members of minority groups especially—have always known: that “truth” is not always an objective principle. Of course there are certain active truths—for example, a water molecule is made up of one oxygen and two hydrogen atoms—but societies are not, and probably never will be, ordered according to scientific precepts. There were, after all, successful societies on Earth before scientific thinking emerged. No, truth in a particular society is not based on fidelity to a suite of facts that can be tested and proven in a laboratory; truth flows from a set of values that have been developed by powerful people over time.

The man smiled again, and I could tell that this was actually his true smile.

Another way of saying this is that one’s relationship with truth is simply a proxy for one’s relationship with power. The powerful and their charges long inhabited a reality in which truth was a relatively stable concept. For them the truth was identifiable and consistent, and its opposite was immediately apparent. Reality was comfortable and comprehensible for this reason, and anyone who lied was aware of the barrier they had breached; they and they alone harbored responsibility for their failures, and if they simply exhibited a willingness to play by the rules all would be right for them once more.

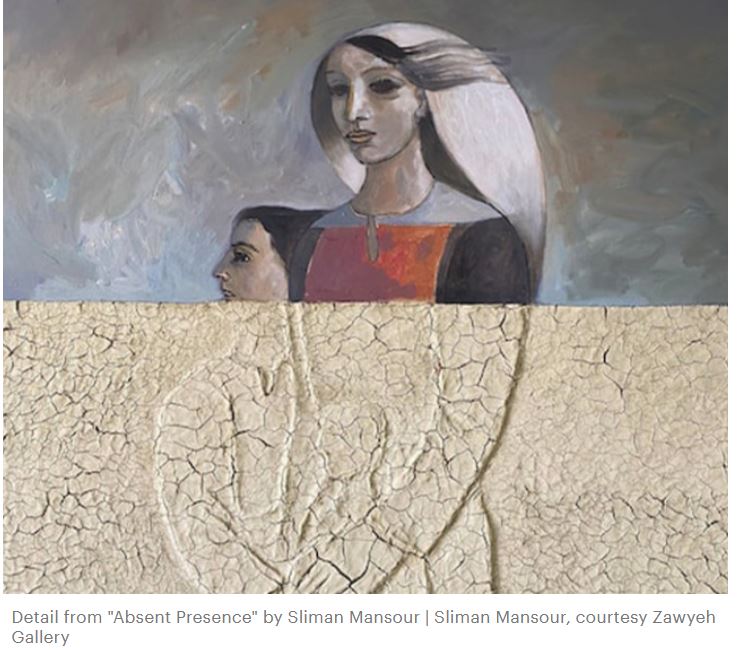

For the marginalized and dispossessed, however, truth has always been a moving target. Consider for a moment the plight of a Black man who has been falsely accused of a crime because of the color of his skin. Or the Indigenous American groups whose treaty with the federal government have been broken. Or the woman who spends years trying to convince the authorities she was raped. Or the immigrant who is forced to part with his earnings simply because his customer tells him to. These people and millions more have inhabited a realm in which alternative facts weren’t extraordinary or unexpected but simply an inevitable component of their engagement with reality. They understood they would often encounter situations in which external truths, imposed and enforced by the powerful, would supplant their own truths, and their truths would be converted into lies.

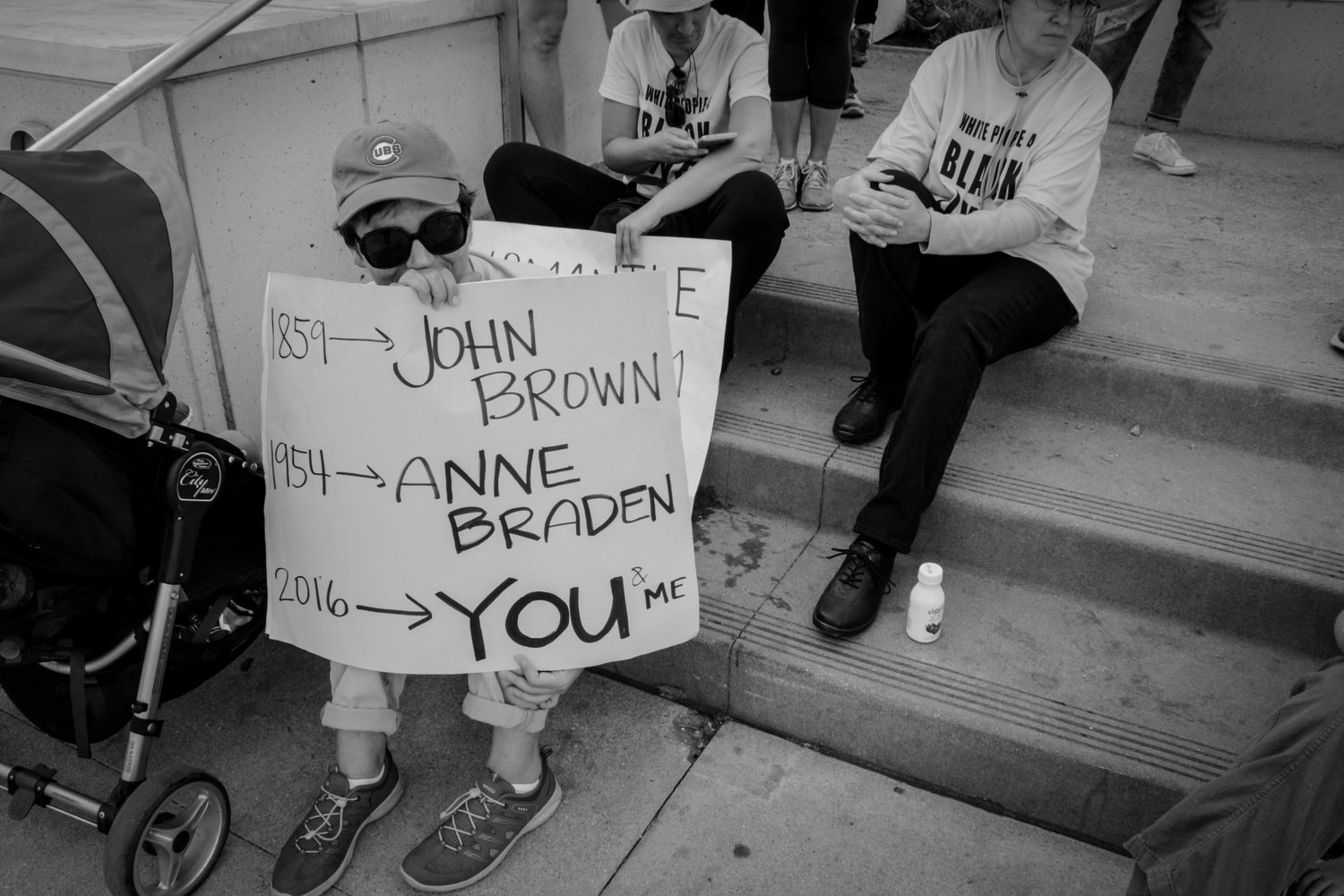

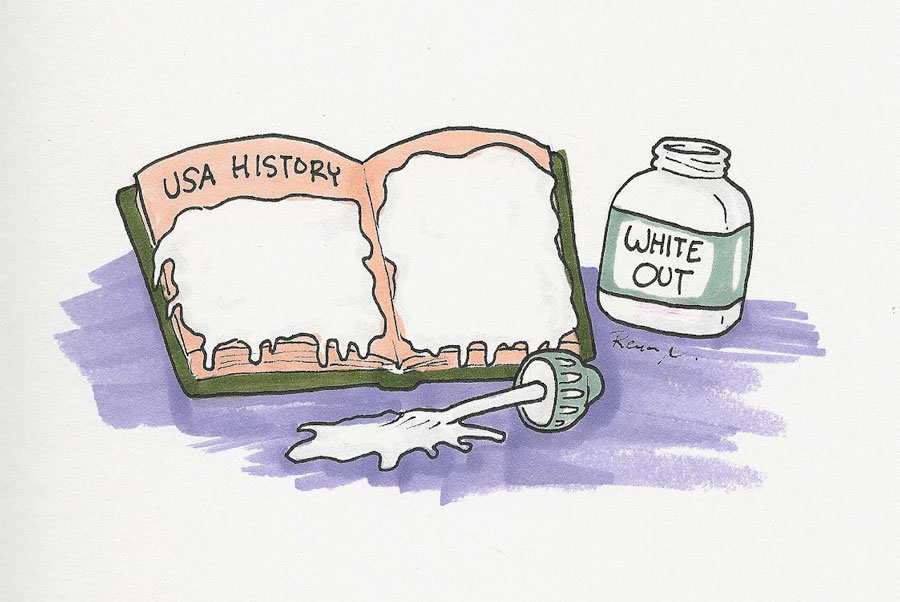

For those who benefitted from the American conception of truth, the idea of truth was bound with a corresponding belief in the intrinsic goodness of the American project. This belief was grounded in a series of narratives about America’s formation that positioned the colonialists as underdog heroes who vanquished oppressive enemies, and the founding fathers as moral men who established a new republic based on progressive ideals such as universal equality. The belief was sustained by the creeds that emerged from these narratives, such as American exceptionalism and the American Dream. Historical events that undermined these creeds, such as the brutal suppression of the indigenous population of America, or the fact that many of the founding fathers were slaveholders, were minimized or explained away as the understandable actions of men of their time. As a result, the Americans who benefitted from these creeds, mainly white Americans, chose to ignore, disbelieve, or moderate any contradicting information they received. This practice extended to our adventures abroad as well, and the worst sins we committed around the world—political assassinations, illegal war, collateral damage—were invariably described as justified actions by a government that was mainly interested in the pursuit of good.

Many Americans based their understanding of reality—of what was true, and what was not—on the belief that America was a fundamentally moral place. One objective of the various social justice movements of the twentieth century—the women’s suffrage movement, the civil rights movement, and the labor rights movement among many others—was to challenge this idea. Civil rights activists adopted the practice of staging protests that attracted authorities who conducted themselves in immoral ways; images of these protests and their brutal aftereffects were beamed across the country and validated the claims that Black Americans had been making for centuries. Historians began to interrogate America’s foundational narratives. They unearthed evidence that our founding fathers had not always lived by the ideals they had so enthusiastically espoused. Though many Americans continued to believe that America was and had always been a moral country, others recognized that they would have to reshape their sense of reality—and their corresponding understanding of truth—to account for what they had learned.

The consequence of these developments (and many more, including our misadventures in Vietnam) was that—slowly—some Americans began to decouple their understanding of reality from the notion that America was intrinsically good. Their evaluation of reality was guided by a more nuanced understanding of American history and its enduring effects on marginalized populations. As time passed, a determination about the truthfulness of a particular claim was less likely to be guided—or you could say shrouded—by a belief that the powerful were acting according to moral principles that were designed to benefit everyone.

This evolution in the relationship between truth and power represented an obvious threat to elites who benefitted from the status quo. Their immediate response was to protect the status quo; to insist that their claims about American history, capitalism, racism (or, according to them, the lack thereof), and power were all true because America was good. Two critical events during George W. Bush’s presidency epitomize this trend: his decision to initiate a war with Iraq, and his government’s response to Hurricane Katrina.

In the case of Iraq, the thrust of Bush’s argument, based largely on false evidence that Iraq was stockpiling weapons of mass destruction, was that his administration had an obligation to rid the world of a despot who was committed to harming America and his own people. In other words, Bush asked Americans to trust he was invading Iraq for morally justifiable reasons. Bush failed to mention any other motivation for invasion, such as our desire to secure Iraq’s oil reserves. In the case of Katrina, an event that disproportionately battered Americans of color, Bush assured Americans that his administration would use the recovery as an opportunity to address longstanding racial and economic inequality issues in the region, a promise that contained within it echoes of earlier promises by earlier leaders to atone for America’s mistreatment of African Americans. Sixteen years on, it has become clear that the recovery, overseen by the federal and local governments, has only exacerbated those issues. In light of these and many other events, the moral force of the arguments made by the powerful waned as more evidence—both historical and contemporary—emerged that the protection and projection of power, and not hazy notions of goodness or morality, has largely been the guiding force in American life.

White Elephants

And then came Donald Trump. One reason he achieved success so quickly is that he offered Americans with cultural and economic power—in particular white men and women—a method of maintaining their power by reversing the relationship between morality and truth. His gambit: instead of arguing that a claim was true because of the goodness of America, he premised his case on the idea that Americans who defend what might be called traditional truths about America are good.

For the marginalized and dispossessed, truth has always been a moving target.

The through line of the various cultural foments initiated or amplified by Trump, including his Muslim ban (“we have no choice”), and his defense of the Charlottesville rioters (“very fine people”), is that his supporters need not feel any guilt or hesitation about upholding their traditional beliefs, like the importance of maintaining a predominantly white and Christian American population, or the truths that flow from these beliefs, like the idea that immigrants from non-European countries are more likely to be criminals than their European counterparts, or that reverse racism exists. To the contrary, Trump’s “Make America Great Again” rhetoric provided his followers with the confidence that they occupied the moral high ground because they were committed to moving American culture back in time to an era when American greatness was more or less unquestioned and America’s ability to do great things (according to them, anyway) was unmatched.

This was an especially effective political maneuver because Trump removed the truth from the realm of evidence and verification. The truth no longer had to be defended or proven and, more important, the truth as they conceived it could no longer be threatened by those who offered contradictory evidence because the truth now existed in some realm beyond evidence. The truth was the truth, self-evident and immune to counterargument, and anyone who believed otherwise had to be defeated, politically or otherwise.

Trump’s political opponents frequently commented on his habit of lying, yet they offered rhetoric that seemed just as inaccurate. During her second presidential debate against Donald Trump in 2016, Hillary Clinton argued that America was great “because we are good.” In other words, her efforts at countering Trump’s divisive rhetoric were grounded in the same unquestioning belief in American morality that had long been a staple of American political rhetoric and a core element of the American definition of truth before Trump. During the past four years, Biden was among many politicians who offered an iteration of Clinton’s statement in response to Trump’s actions: “this is not who we are,” they constantly intoned, as if diverging histories of the various inhabitants of this country could be neatly captured in six small words.

In America, “we” is a presumptuous term. It is deployed by politicians to unify us, to connect us to one another, yet so much is lost when it is flippantly used to reference our shared past, an era in which we did not share burdens or bounty equally. “We” becomes a dangerous term when it forms the basis for establishing a shared understanding of truth, a version of truth that often benefits whiteness and entrenched power at the expense of everyone else.

Trump’s version of the truth is so intoxicating for so many because, just like the conception of truth that has existed since the founding of this country, it centers whiteness with the added benefit of being immune to counterevidence or critique. Trump provided his followers with a seemingly failsafe method for perpetuating the past into the future: simply insist, Trump argued in his own inimitable way, that the truth is the truth because it has always been the truth. A rejoinder that relies on the same circular logic, that does not peer deep into history beyond the myths that have defined us, will inevitably fail simply because it cannot be as compelling and persuasive as a version of truth that permits the powerful to simply ignore the problems of the past.

The most startling and inevitable consequence of Trump’s reconceptualization of the truth occurred on January 6, 2021, when a mob of his supporters, acting on the idea that the election had been stolen from Trump, stormed the U.S. Capitol. Though many of his supporters knew his claims were without merit, they wagered that Trump’s efforts to destabilize and refashion the meaning of truth had granted them a unique superpower: the ability to simply overlay their ideal version of reality on the reality we currently share. While some tech bros and Wall Street speculators are convinced that virtual and augmented reality will be among the dominant technologies of the twenty-first century, Trump has proven our reality, shaped as it is by a pervasive commitment to the maintenance of order and an awareness of how earlier societies succumbed to destructive mobs, remains eminently manipulable, and you don’t need a complicated algorithm to change things. You simply need to believe. Or act as if you believe. And while many of us celebrate the gains that various groups have made by scrupulously adhering to the rules, by gathering evidence of historical wrongs and offering statistical proof of contemporary discrimination, the Capitol rioters demonstrated how a small, determined group of people might go about changing the rules altogether, especially if their efforts are underwritten by media networks that are willing to perpetuate lies until they become gospel. Here’s the truth: we can never take “we” for granted; we must build toward it. And we cannot passively accept lofty rhetoric that seeks to bind us without accounting for how much many of us have suffered.

To this day I still think of the moment when my father’s customer stole money from him, and the moment, only a few days later, when we saw him again. This time my two younger siblings were in the van with us, and the man was accompanied by his daughter. He spoke with my father as if they were great friends, and my father responded in kind. When the man left my father did not respond to the look I gave him; he simply kept on selling. Now I realize that my father already knew the lesson that the man taught him, and that men like Trump would teach the entire country a several decades later: the meaning of truth is not and has never been fixed. And if you aren’t aware of how the meaning of truth has been constructed in your society, who benefits, and why, the moment might come when someone arrives to inform you that everything you know is a lie.