(Source: Media Lens)

Some comments so perfectly capture the blinkered naivety of corporate journalism that they remain fixed in the mind for years and decades. Twenty years ago, I was leafing through a copy of the Guardian when this jumped out at me from journalist Simon Hoggart:

Some comments so perfectly capture the blinkered naivety of corporate journalism that they remain fixed in the mind for years and decades. Twenty years ago, I was leafing through a copy of the Guardian when this jumped out at me from journalist Simon Hoggart:

'all religion is bonkers and irrational. If it wasn't bonkers and irrational, everyone in the world would believe it, and it would be called common sense'. (Simon Hoggart, 'Bad karma from Vlad the Impaler,' Guardian, 2 February 1999)

Like me, you may have a good deal of sympathy with the first part of this statement – most of what we call 'religion' is indeed 'bonkers and irrational'. But before we cheer too loudly, let's run the assertion past Noam Chomsky's All-Purpose Reality Checker for understanding 'mainstream' culture:

'The basic principle, rarely violated, is that what conflicts with the requirements of power and privilege does not exist.' (Chomsky, 'Deterring Democracy', Hill and Wang, 1992, p.79)

Chomsky's argument is that important facts, ideas, sources, indeed whole frameworks of understanding, are simply ignored by 'mainstream' media, politics and culture when they conflict with elite interests. Our media alert archive is packed with numerous shocking examples.

And sure enough, it turns out that the versions of religion that exist for the 'mainstream' are perfectly compatible with the 'requirements of power and privilege'. These are the kinds that encourage irrational desire (for heaven) and irrational fear (of hell), blind obedience ('faith'), deference to authority (we are 'sheep' to the 'Lord' and His 'shepherd'), with morality delivered from on high via tablets of stone and 'holy' scripture, rather than investigated, evaluated, by us, as individuals.

This version of religion fits perfectly with systems of exploitative political power, which also encourage irrational fear (of Official Enemies: 'Reds', immigrants, Corbynites) and desire (for more of everything), and deference to authority (presidential and prime-ministerial idols preserving 'national security'), with morality and Truth largely a matter of following the herd through 'service', 'duty' and 'family values'.

It ought to be astonishing that religious leaders are forever seen literally rubbing shoulders with war-fighting state executives, royal families and military commanders. Mark Twain summed it up well:

'I bring you the stately matron named Christendom, returning bedraggled, besmirched and dishonoured from pirate raids in Kiao-Chou, Manchuria, South Africa and the Philippines, with her soul full of meanness, her pocket full of boodle and her mouth full of pious hypocrisies. Give her the soap and a towel, but hide the looking-glass.' (Mark Twain, quoted, Norman Solomon, 'The Twain That Most Americans Never Meet,' ZNet Commentary, 19 November 1999)

Tolstoy added:

'A Christian nation which engages in war ought, in order to be logical, not only take down the cross from its church steeples, turn the churches to some other use, give the clergy other duties, having first prohibited the teaching of the Gospel, but also ought to abandon all the requirements of morality which flow from Christian law.' (Tolstoy, 'Writings on Civil Disobedience and Non-Violence', New Society Publishers, 1987, p.xiv)

But Hoggart was nevertheless wrong, because the religion that is 'bonkers and irrational' is all that the propaganda system allows us to see. It is all that appears to be, not because there is nothing else, but because the alternative 'conflicts with the requirements of power and privilege', and therefore 'does not exist' for the 'mainstream'.

The psychologist and psychoanalyst Erich Fromm wrote of 'humanistic religion' as opposed to the favoured, irrational version, which he called 'authoritarian' or 'power religion'. It is the former that is almost nowhere to be seen and might even seem to have nothing to do with religion at all.

For example, everyone knows that 'religion' is all about God – a super-being who creates, observes and judges. But this idea of religion – equally praised and reviled by theists and atheists – in fact, is power religion. Humanistic religion is concerned with understanding and dropping the illusion of the ego, with God viewed, not as a supernatural father figure at all, but as a metaphor for the totality of the cosmos experienced in a fundamentally different way after the ego has been dropped. It is about meditation, not prayer. It is about self-awareness through direct experience, not 'faith'. It is thinking for oneself, not obedience. It is primarily experienced through feeling, not understood through thought.

Authentic humanistic religion renders the meditator useless as a tool for pirate raids in Kiao-Chou, Manchuria and South Africa; indeed, for any kind of subservience to authority. Naturally, then, in accordance with Chomsky's Reality Checker, this kind of religion 'does not exist'.

Crucially – and this may seem profoundly counter-intuitive - because it is rooted in feeling, humanistic religion is not interested in endless cogitating about abstract, metaphysical issues. It has nothing to with the 'supernatural', nor even with the extraordinary. Instead, it is about diving deeply into the ordinary. It is rooted in real, sweaty, flesh-and-blood life. It emerges, quite naturally, out of a determined search for ordinary answers to ordinary problems. Therefore, the great metaphor for humanistic religion is the pristine lotus emerging out of muddy water. Let's take a leap into the mud and see what might emerge from it.

Thought Factory – The Night Shift

Consider insomnia: when we have difficulty sleeping, many of us find it natural to reach for sleeping pills. We can't sleep, we need to sleep, so we buy some pills that help us sleep. Simple.

Highly influential pharmaceutical companies are delighted for us to respond this way; they spend a lot of money urging doctors to push pills. This is the reverse side of Chomsky's coin – pills that 'solve' (or ideally, suppressrather than completely remove) problems are highly compatible 'with the requirements of power and privilege'. And so, like power religion, they exist in abundance.

The problem with this solution is that depending on external support of any kind can make us less confident in relying on ourselves: we can become either psychologically or physically dependent. When we become dependent, we can end up stuck on pills and their side-effects (drowsiness, listlessness, reluctance to exercise, and so on) for years, perhaps permanently.

But there is another way of responding to this kind of problem. We can view our insomnia as a psycho-physical-spiritual-political challenge. We can plunge into the problem, chew on it, try to work it out. We can decide to experiment with solutions.

So, to take obvious examples, we can accept that we are unable to sleep on a given night, suffer through it, resist the powerful urge to take a nap the next day (the key to overcoming jet lag) and see if that held-over tiredness helps us the next night. Of course, that doesn't address the fact that we feel grim the morning after we didn't sleep, although there is consolation in the fact that we can perform well without sleep (Olympic rowing champion Steve Redgrave revealed that he won a gold medal on no sleep). We can give up day-time naps permanently or shorten them drastically. We can take exercise to release excess energy and tire the body. We can stop drinking tea and coffee after lunch. We can stop drinking them at all.

Alcohol, viewed by many as the insomniac's faithful friend, is a big negative factor – it certainly helps us drop off, but when we wake up in the dead of night, it can act like petrol fuelling a fire of anxious feelings and thoughts keeping us awake for hours. Alcohol causes adrenaline and cortisol to be released in the body – when the alcohol wears off, these stimulants come to the fore and keep us awake. Annie Grice writes:

'Here's the thing – any amount of alcohol will disrupt your sleep. It doesn't matter if you have one drink or you go on a margarita binge-fest. You're not going to sleep well. If you do this night after night, the lack of quality sleep cycles will begin to take its toll.' (Grice, 'The Alcohol Experiment', HQ, e-book version, 2018, p.734)

We can experiment with all of this and come to realise that, while physical issues may certainly be a factor, it is often compulsive thinking that keeps us awake. In fact, we can see that the mind operates like a thought factory that hammers away deep into the night, torturing us for hours. Anyone who has revised too hard for an exam, or worked too hard on a piece of writing, knows that the momentum generated by an overworked brain can defy all efforts to stem the flow of thoughts. And the longer we are awake, the darker and more fearful the thoughts become. At this point, it is understandable that people are tempted to club themselves over the head with a shot of the hard stuff, or a pill.

But if we start to identify compulsive thinking as a problem, we have reached a significant point in our investigations. After all, up to this point, we have identified strongly with the voice in our head: 'My name's David.' That voice in my head is 'me', isn't it? And yet all is not as it seems. If I can be aware of the thoughts in my head, if I am able to identify thought as a cause of suffering, then who or what is the 'I' that is aware? Is it also thought?

In fact, it is clearly not, itself, thought. Rather, it is the consciousness that is aware of thought. I am watching the thoughts rolling out of some invisible factory. I am the awareness that perceives thought. Thoughts are not aware. The thought, 'Four o'clock, and I still can't sleep!' is not aware; it is just a packet of information. It has no more awareness than an email or a telegram. Thoughts are dry, dead signals, whereas I am aware of them. I have juicy, alive awareness - I am awareness that perceives thoughts.

I could have taken a pill, but this is interesting: if I am awareness, separate from thought, then perhaps I can redirect awareness away from thought. Might that help?

We can now experiment with focusing attention away from this babbling mind. We can direct attention from thought to sensations in our hands, or in our feet, or the breath rising and falling in our chests. For example, we can pay attention to the feeling of our hands tingling, pulsing. We can just keep placing our attention in our hands. We notice that when we focus on these feelings, thoughts subside. We notice that when we direct attention back to thoughts, the thought factory surges back to life. When we turn our focus back to the sensations in our hands, feet and chest, thoughts again subside to a trickle.

A problem arises when particularly energetic thoughts driven by intense emotion keep pulling us back into the mind. In this case, we can hop on a kind of meditational roundabout by focusing attention on our left hand and think 'left hand, relax', and try to feel the hand relax. Then think 'left foot, relax' and try to feel it relax, then 'right foot, relax', then 'right hand, relax', then 'left hand, relax' again, and continue in a circle. We say the words in our mind, but the key thing is to feel the hand or foot relax, to place our attention there for a second or two. This is robotic and boring, and sleep-inducing; but it is, above all, a very effective method of shutting out the disturbing, compulsive thoughts that keep us awake – awareness simply doesn't have time to pay attention to them.

As we're experimenting with this redirecting of attention, we may be astonished to find a ripple of sleepiness passing through our body. We may even find ourselves waking up many hours later. At this point, it becomes overwhelmingly obvious that excessive thinking is a big problem – the moment we turn away from thought, even for a few moments, sleep starts to seep in. If the meditational roundabout fails, we can just encourage each part of the body to relax, focus on relaxing rather than sleeping. Of course, it is often precisely because we are trying so hard to get to sleep that we can't sleep. The moment we give up trying, we fall asleep!

By investigating insomnia in this way, rather than trying to suppress the problem, we have stumbled across meditation. Meditation simply involves directing attention away from thoughts, depriving them of energy, so that the mind calms down, so that there is greater peace as thoughts subside. This is often called 'mindfulness', but in fact it is mind emptiness that arises when we focus away from thought.

Similar awareness can arise out of investigating other forms of suffering. For example, what we call 'panic attacks' are not, in fact, 'attacks' at all – nobody is attacking anybody. What actually happens is that unnerving thoughts arise: 'This train is packed, I can't breathe or move. I'm trapped!' This triggers an adrenaline reaction, which is unexpected and seems completely inappropriate, as if we are losing our minds. The mixture of panicky thoughts and adrenaline triggers more panicky thoughts – a sufferer can feel as though they must escape, as if their very life is at stake. This is less an 'attack', more a thought-anxiety spiral: thought generates anxiety, which generates more thought, which generates more anxiety. A single event can have long-lasting effects, causing people to avoid underground trains, buses, planes, cinemas and so on for the rest of their lives for fear of a repetition.

A very powerful remedy, again, is meditation. We direct attention away from the anxious thoughts – 'I feel awful, I have to get out of here' - to the physical symptoms of anxiety. When we feel the adrenaline, we watch and feel that dark surge of energy pouring into the chest as intensely as possible. When the adrenaline starts the heart racing, we focus on how the heart is beating faster, stronger; and we watch our lungs breathing in and out in response. The more we watch these feelings of panic, the less we are focused on the thoughts driving the panic. Without attention, thoughts cannot arise and proliferate, so they fall away, so the thought-emotion vicious cycle is broken and the symptoms of anxiety also fall away. This has been compared to jumping into the mouth of a chasing tiger. It is dramatically effective and has been understood for thousands of years.

This shift in attention can end, not just a particular panic attack, but the fear of panic attacks in the future. It ends the dread thought, 'I have to get out of here!', because we know that, in fact, we don't need to get 'out of here'; we just need to get out of our thoughts and into our feelings.

Disidentification – 'I Love My Country'

Humanistic religious understanding has arisen out of engagement with ordinary problems like insomnia and social anxiety for millennia. Through a process of trial and error, solutions are found by disengaging from thought and engaging with feeling - a type of meditation.

The mystic George Gurdjieff summarised his teaching with a single word: 'disidentification'. For example, when someone thinks the thought, 'I'm a professional journalist', they are likely identifying with that profession and with the work they produce. The profession and work become genuinely incorporated into an extended sense of self. Thus, when someone criticises their profession or their work, journalists feel as though they themselves are under personal attack.

The same is very obviously the case when someone thinks in terms of 'my car'. They identify with the car and absorb the car into an extended sense of self. They are now comparing 'my car' with other cars as if comparing themselves. If someone scratches or insults, or reveals the limitations of 'my car', they feel deeply wounded. When 'my team' is unfairly robbed of a just result by a football referee's clear bias, fans are incandescent with rage, as if they have themselves been scalded by some grave injustice. If someone insults 'my country', 'my flag', 'my President', 'my religion' and so on, people erupt as if they have been personally attacked. In the 1980s, I ruined a night out by suggesting to a group of US Americans that 'their' then President, Ronald Reagan, was afflicted by a mental illness, which was indeed the case. They reacted as if I had falsely declared them mentally ill.

Disidentification involves recognising that these emotional reactions are rooted in identification with thoughts. In reality, I am not 'my country', I am awareness that observes thoughts like, 'I love my country'. Awareness has no country, no car, no football team. It is a separate phenomenon, just as a mirror is a separate phenomenon from everything reflected in it. We can intellectually disidentify from our emotional reaction to an insult to our extended sense of self. Instead of thinking, 'I'm angry', we can think, 'My mind is angry', or even better, 'I am aware there is anger in the mind.' We are thus disidentifying from the thought, the emotion and the thinking mind itself.

But as discussed, the simplest way to disidentify from thought is to direct attention away from thought into feeling. When we think, 'I'm angry', we are identifying with thought, mind and emotion. But when we take attention into the body and feel the anger, we create a separation, a gap – we are clearly the observer watchingthe emotion, so we cannot be the anger. The moment we pay attention to feelings of anger rather than the thoughts fuelling them, the anger starts to cool. Whenever we experience a flash of anger, we can take a moment to glance inwards and feel the anger, and immediately gain more freedom in responding to the emotion. As discussed, the same is true of anxiety, and other emotions like jealousy, sadness, desire and so on.

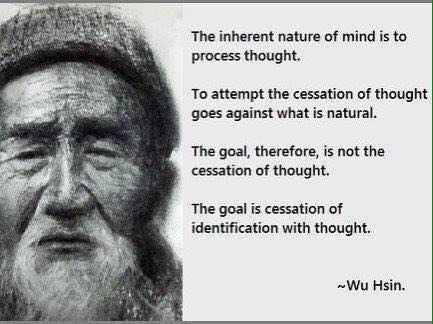

Meditation, humanistic religion, is above all concerned with this disidentification from thought – we stop identifying with the thoughts in our head and start identifying with the awareness that perceives the thoughts. Disidentifying from thought is disidentifying from ego (which is a conglomeration of thoughts), the ultimate cause of our woes.

Beyond all the 'bonkers and irrational' nonsense talked about religion, precisely this, in fact, is the focus of all the enlightened mystics throughout the ages: Buddha, Bodhidharma, Chuang Tzu, Gurdjieff, Hakim Sanai, Heraclitus, Ikkyu, Jesus, Kabir, Krishna, Lai-Khur, Lao tse, Lao tzu, Lazy An, Maharshi, Mahavir, Mansoor, Meister Eckhart, Meera, Nanak, Osho, Patanjali, Rabia, Ramakrishna, Saraha, Tolle, Yoka.

Most of us have no idea that this was their real message – indeed, many or most of their names are unknown to us. And this is the greatest tragedy, the worst example of 'mainstream' filtering, because their message is a great humanising force for awareness, love and compassion.

Why is it ignored? Because the 'basic principle, rarely violated, is that what conflicts with the requirements of power and privilege does not exist'.

No comments:

Post a Comment